Enhance Your Change Agility

Game Changing Workshops that Align your Organisation

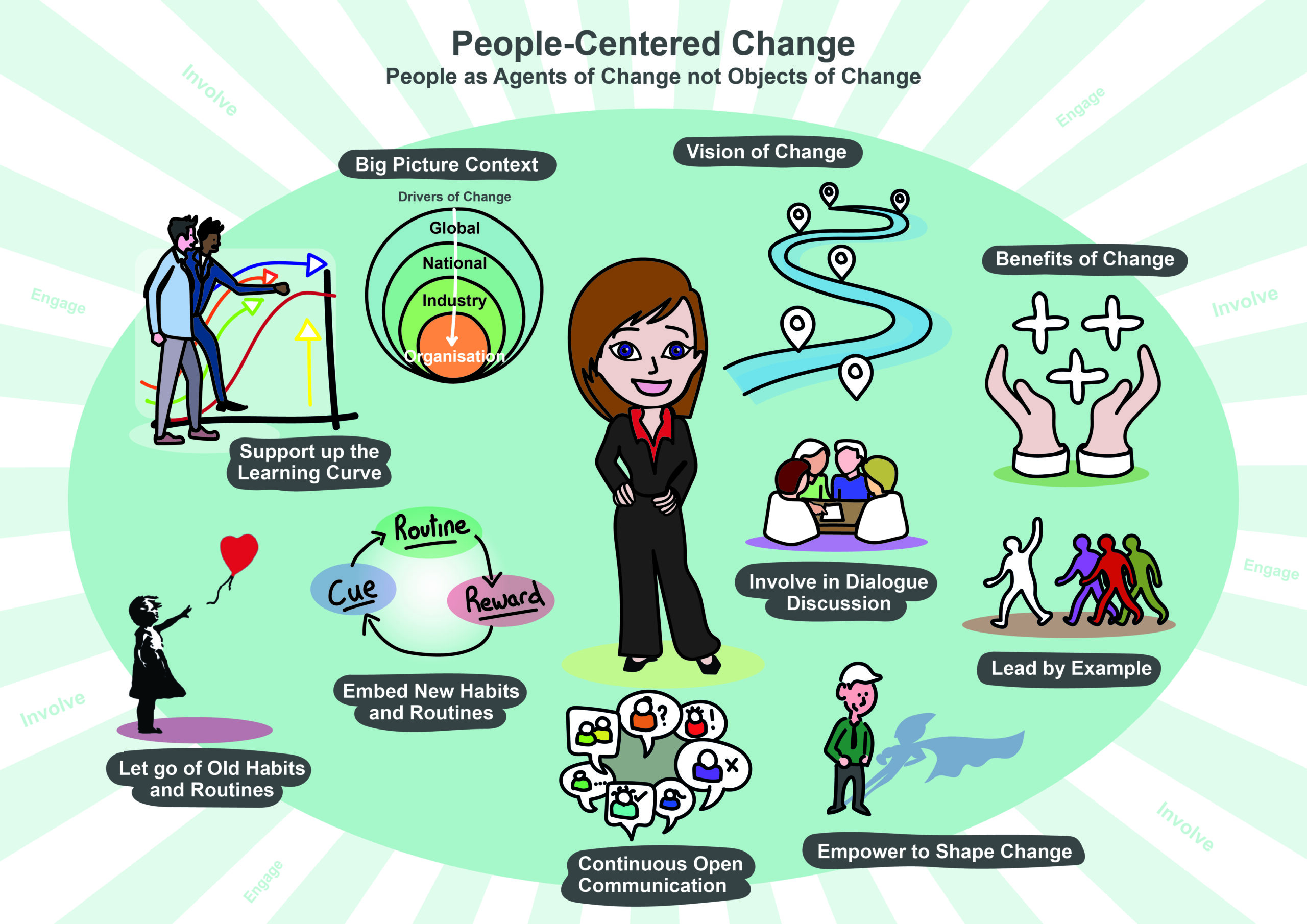

Change initiatives frequently stall, not from a lack of vision, but from active resistance. What if your leadership team was equipped to make this resistance virtually disappear? What if your employees were not just compliant, but genuinely excited to own the shift and make it stick?

Our proprietary approach is built on a fundamental insight: When leaders understand and address five core human needs at every stage of transition, they unlock a natural capacity for adaptation, turning anxiety into commitment. Change then transforms from something people endure into something they actively drive.

The 5 Forces of Change – training workshops, coaching, and resources

This framework is your solution. Our training workshops, coaching, and resources empower senior leaders, managers, and employees to meet everyone’s fundamental needs for: Certainty, Purpose, Control, Connection, and Success. By focusing on these human drivers, you achieve a collective mindset shift that boosts adaptability, minimises friction, and delivers dramatic, step-change performance improvement.